Wrigley Institute research leads to unique plastics recycling experiment for high schoolers

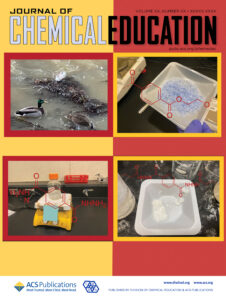

A USC-led team of researchers has developed the first-ever lab exercise for high school chemistry students to practice the chemical breakdown and remanufacture of the polymers that make up PET plastics. A paper on the exercise, “A Polymer Degradation and Remanufacturing Experiment in the High School Classroom,” was recently published as a cover article in the Journal of Chemical Education, a publication of the American Chemical Society.

A USC-led team of researchers has developed the first-ever lab exercise for high school chemistry students to practice the chemical breakdown and remanufacture of the polymers that make up PET plastics. A paper on the exercise, “A Polymer Degradation and Remanufacturing Experiment in the High School Classroom,” was recently published as a cover article in the Journal of Chemical Education, a publication of the American Chemical Society.

The lab exercise grew out of Professor of Chemistry Travis Williams’s research, which investigates novel ways to recycle and reuse single-use plastics. Williams, who is also a long-time volunteer with Boy Scouts of America, frequently takes scout troops to Santa Catalina Island to collect waste plastics that wash up on the beach there. He takes the plastics back to his lab to be used as raw material in experiments. These include his work with Professor of Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Sciences Clay C. C. Wang on turning waste plastics into life-saving medicines. (Watch ABC7’s news story on this project >>)

At the request of the USC Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability, which helps support Williams’s research, Williams and Ph.D. student Justin Lim created a demonstration to show members of the public how chemical recycling of these waste plastics works. They and other members of Williams’s lab debuted the demonstration at the annual Avalon Harbor Underwater Cleanup, so that cleanup participants could see what might happen to the plastic trash they were bringing up from the bottom of Avalon Harbor.

But high school student and Boy Scout E. Aaron Martinez, who had met Williams while helping to collect plastics on Catalina Island, had an idea to make the demonstration even bigger. A member of the class of 2025 at the Polytechnic School in Pasadena, Martinez was looking for an out-of-the-ordinary option for his upcoming Eagle Scout project.

“Most Eagle Scout projects involve construction, like building a park bench. But I knew from a young age I was interested in chemistry and went to Boy Scout camp on Catalina Island because they teach chemistry there. This seemed like the perfect opportunity to do something chemistry-related for my Eagle Scout project,” Martinez says.

According to the Boy Scouts, only about 6 percent of Boy Scouts become Eagle Scouts, the organization’s highest rank. The culminating project is a key part of Eagle Scout requirements and must be organized and led entirely by the scout who is applying for Eagle rank. It also must provide some kind of service to the scout’s community.

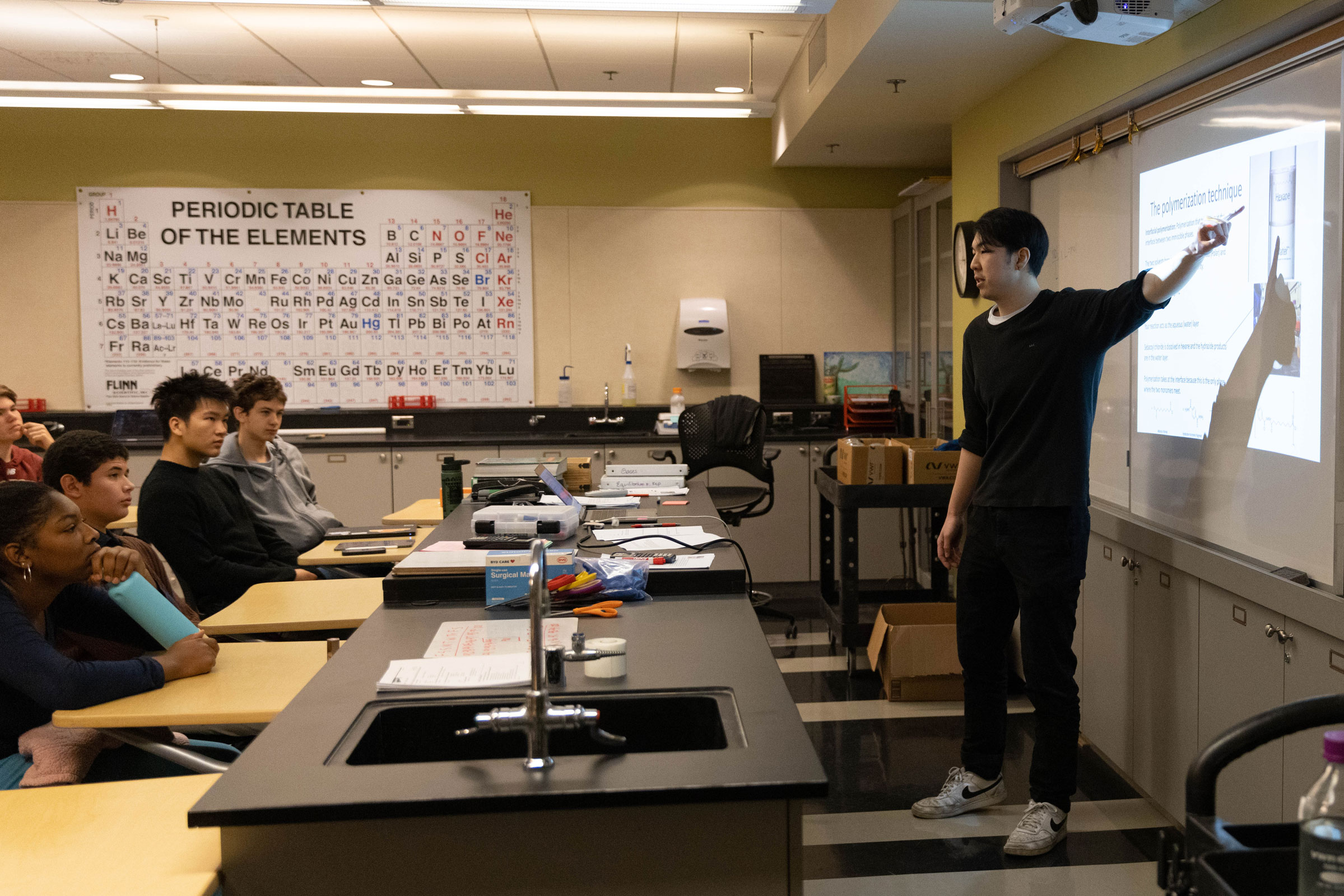

To meet these requirements, Martinez worked with Williams and Lim to design a second demonstration stage that shows how the monomers created through the original chemical reaction can be reconstituted into a new polymer. He then organized the collection and sorting of more than 138 pounds of trash from Pasadena’s landmark Arroyo Seco in order to obtain raw materials for the demonstration. Finally, he approached his chemistry teacher, Robin Barnes, and obtained her buy-in for her students to complete the demonstration during their lab period. The overall goal was to increase high schoolers’ exposure to polymer science, which in turn can help make them more supportive of recycling programs in their communities.

With assistance from Ph.D. student Lim, Barnes identified connections between the demonstration and her curriculum so that she could tease out the implications of the exercise for her students. Lim then spent two days at Polytechnic, leading the demonstration with Martinez’s class and two other chemistry sections.

“The students are going to have a lot of pride in the fact that they were the first class that did this exercise. I think it’s a really exciting scientific process that connects with real life. Often the point of a lab is to teach a concept, but this has tangible value to it,” Barnes says.

For Martinez, the whole experience was eye-opening. Without the demonstration, he says, he would not have seen the process firsthand, understood how it works, or even known it was possible. That spark of understanding is the ultimate payoff for Williams, who is always looking for ways to reach young people with the power of science to solve the problems caused by climate change.

“Showing the students that you can not only break down these plastics but also convert them into something else, that’s crucial to helping them understand the importance of recycling,” Williams says.

The research behind the polymer demonstration was supported by National Science Foundation grants CHE-1856395 and CMMI-2227649 and by the Wrigley Institute. Authors on the paper referenced in this story are Y. Justin Lim, Brandon Wong, Katie Macfee, Alexa Cueva, E. Aaron Martinez, Cameron Paxton, Robin Barnes, Eric Kleinsasser, and Travis J. Williams.