Rain, Wind, Wildfire Ash: The Santa Susana Field Lab and Community Risk Perceptions

How does a poet end up designing a community risk perception study?

The answer begins with an errant powerline and a dry field. It’s November 8, 2018, Santa Ana winds reaching the speed of slow cars in light traffic. As the Woolsey Fire takes hold, my mother takes a photo of the burning ridge from our driveway. We’re packing the car now, she texts.

I picture my childhood home burning, as if experiencing loss in theory could make the actual loss easier in practice. Over the next few days, my parents remain one block from the evacuation zone. The house is fine, but it keeps burning in my head for months, and when I finally start the creative manuscript that is now central to my dissertation, I’m not thinking about risk perception studies. I’m thinking about the intersection between confessional poetry and eco-poetry, how personal and familial histories might be rendered through the lens of anthropogenic climate catastrophe.

Two years and many drafts later, I schedule a biopsy for the sore on my lip, the one that waxes and wanes but never fully heals. By now, I’ve learned that the Woolsey fire started on the grounds of the Santa Susana Field Lab (SSFL), site of the worst nuclear disaster in U.S. History, 4.8 miles from the house that didn’t burn. I’ve learned rocket fuel was illegally dumped there for decades, that more than one meltdown occurred. Some parcels of SSFL land are so contaminated that, were you to plant a garden there, were you to consume its produce, your lifetime chance of developing cancer would be 90 percent. Wildfire transformed vegetation growing on these parcels into particulate matter, and embers can drift as far as 24 miles. Of the four children raised in my family’s home, two have already been diagnosed with different cancers. My doctor calls with biopsy results. First ovarian, then cervical, now skin.

My name is Leah Tieger, I’m a fourth-year doctoral candidate in English, and I haven’t studied a “hard” science in over a decade. Still, as Phil Brown notes in Contested Illnesses: Citizens, Science, and Health Social Movements, “virtually all cases of contaminated communities are detected by residents.” Lived experience becomes secondary to quantitative data in this context, and even if that wasn’t the case, geographical cancer clusters and environmentally induced illnesses are almost impossible to prove on an empirical level. My risk perception study arises from and within this impossibility. How do members of my contaminated community simultaneously navigate the tension between subjective experience and objective data? What role do lived experiences play in cultural constructions of knowledge? How can those constructions be directed toward changes in public policy?

Funding from the Sonosky Environmental Sustainability Graduate Fellowship allowed me to devote my summer to an independent study in survey design. This approach informed my threads of inquiry along the following lines:

- Risk perception as impacted by geographical proximity to the SSFL

- Risk perception as impacted by household health

- Links between risk perception and risk mitigation behaviors

- Links between risk perception and community engagement/activism

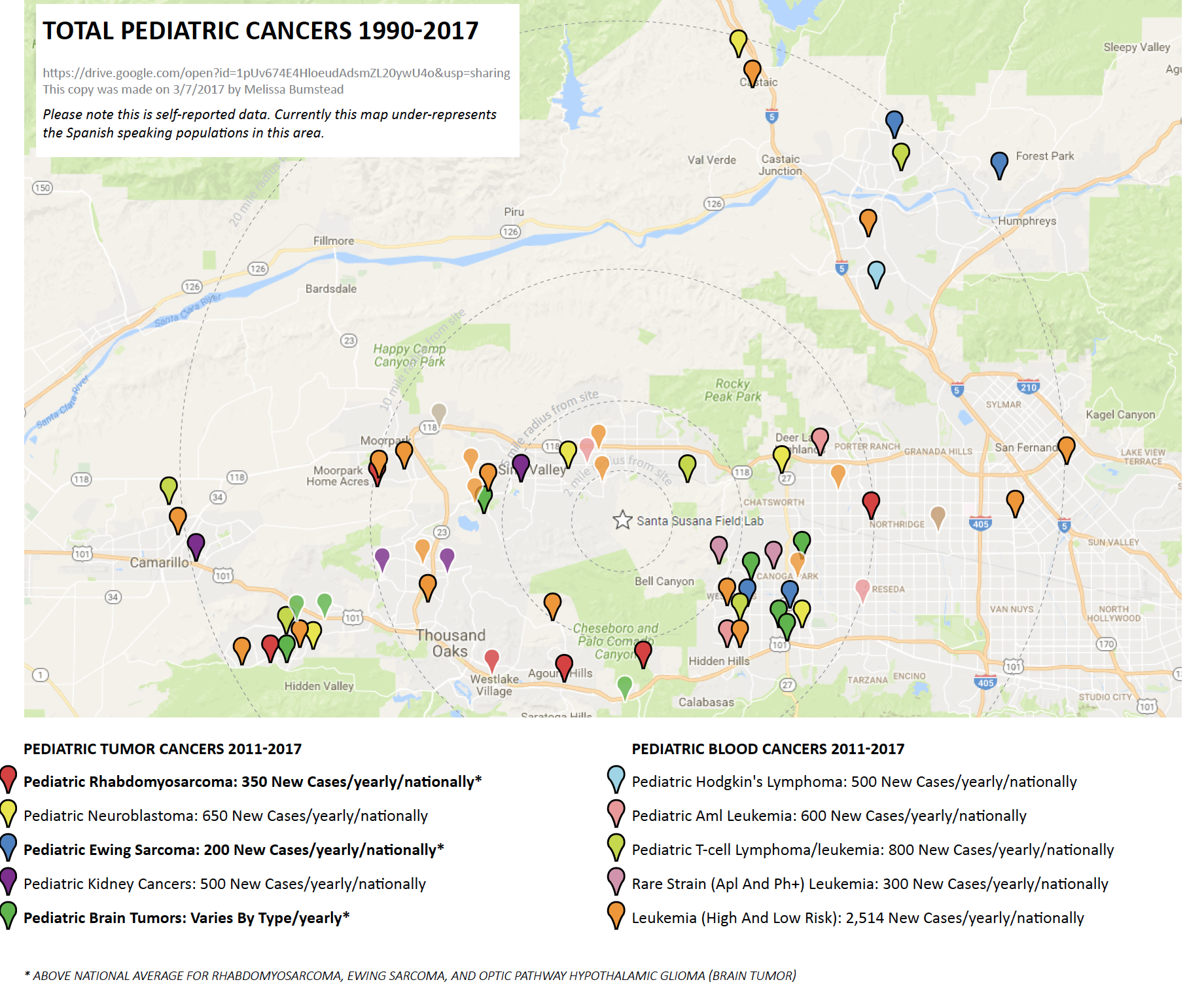

Community engagement is the driving force in SSFL cleanup efforts, and survey responses can be applied to assist in those efforts. My study identifies residents who wish to become more involved, and responses will be used to inform planning and strategies for ongoing public advocacy efforts. To that end, results will be shared with Melissa Bumstead, founder and director of Parents against SSFL. Her trajectory from the mother of a pediatric cancer patient to face of a public movement is the central story of the 2021 documentary In the Dark of the Valley. I’ve invited Bumstead to review my current survey design, and the first round of surveys will be distributed through the Parents against SSFL contact list. While respondents from this list may be more sensitive to risk than other residents, I intend to account for this possibility by sending a second round of surveys to residents by relevant zip code.

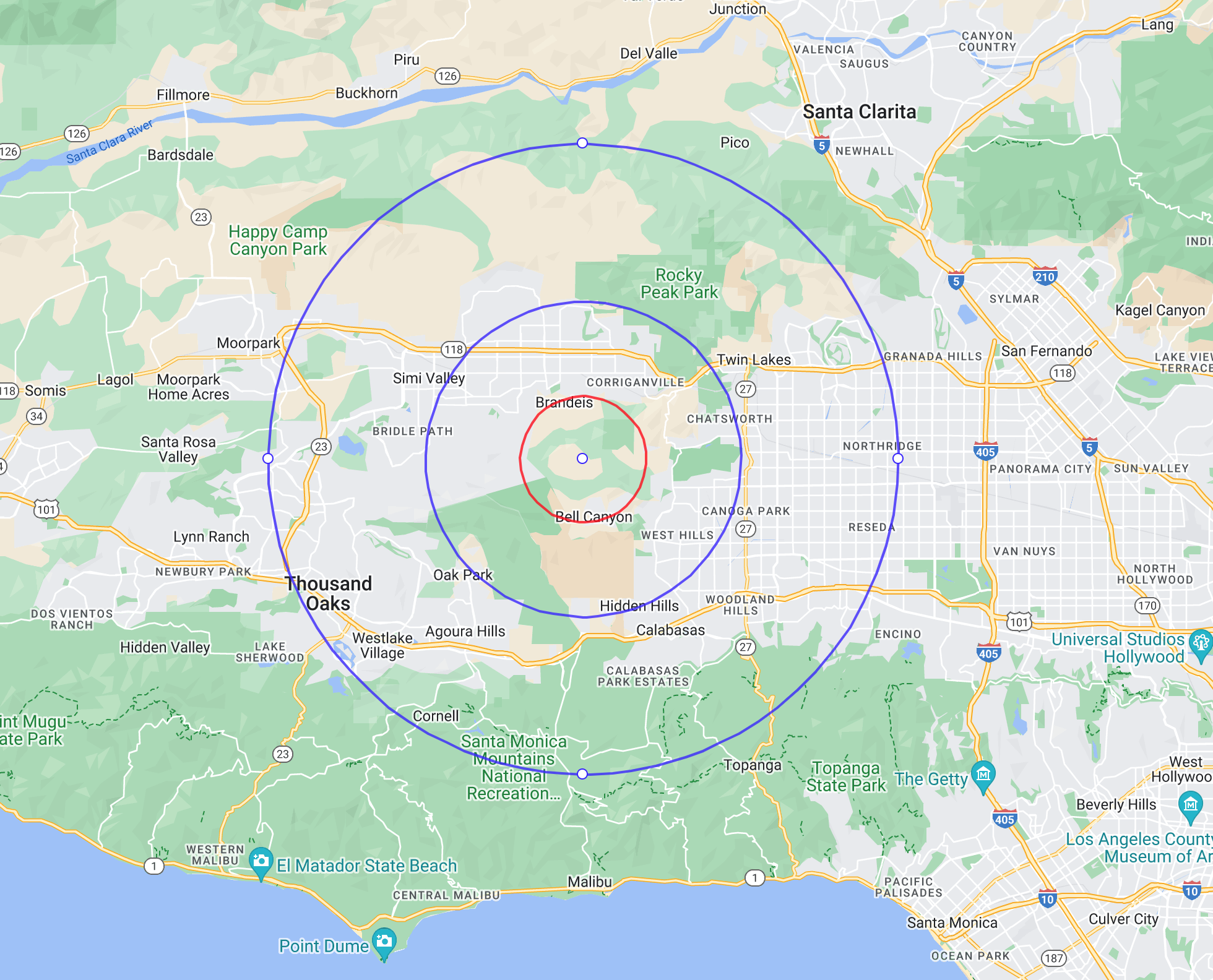

Considering potential migrations of topsoil, water runoff, and wildfire ash, my initial interest is centered on residents living, or having lived, within a ten-mile radius of the SSFL. This radius encompasses highly populated suburbs in both Los Angeles and Ventura Counties, including parts of West Hills, Woodland Hills, Chatsworth, Canoga Park, Thousand Oaks, Simi Valley, Calabasas, and the wealthy enclave of Hidden Hills, where Kim Kardashian resides. Unlike many contaminated communities across the United States, several areas around the SSFL are predominantly white and middle to upper-middle class. Given this socioeconomic anomaly, results from my study might prove useful to researchers in environmental justice and environmental racism, especially when comparing health outcomes, activist engagement, and public policy impacts.

My approach is open-ended and ongoing, and this project extends beyond my fellowship tenure. A third survey round may be sent to eligible respondents in a radius extending from 10.1 to 20 miles. Are these residents more or less likely to actively advocate for cleanup efforts? Could the survey itself open a path toward deeper engagement? Until then, my focus remains on round 1 respondents, inviting volunteers for in-depth personal interviews. This is where the writer in me returns, taking a narrative, ethnographic approach that will inform my latest creative manuscript. Here, I’m particularly interested in awareness and its lack thereof, in vacillations between denial and acceptance. How do community members (affected or not), perceive risk, but also how do they perceive responsibility and accountability. What moves us from belief to action?

Radius map: SSFL (central white circle); 3 miles (red), 5 miles (blue), 10 miles (black)

Radius Map Revisited: Self-Reported Pediatric Cancers, 1990-2017. Compiled by Melissa Bumstead

Leah Tieger is supported by the Diane Sonosky Montgomery and Jerol Sonosky Graduate Fellowship for Environmental Sustainability Research.