The Process of Aging

Let me be upfront – I have not found the secret to eternal youth.

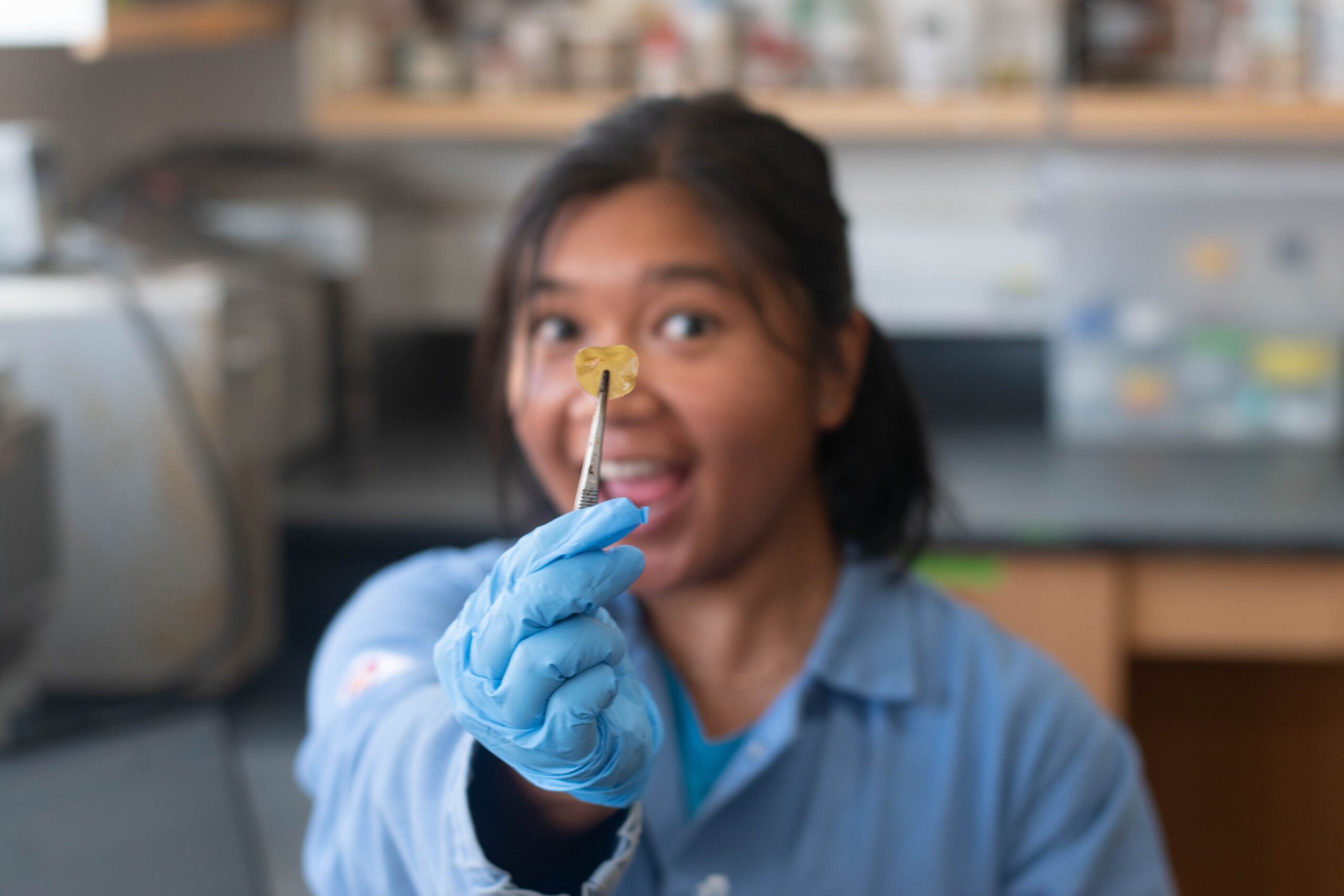

As I rock with the motion of the ocean, floating in the middle of the water column surrounded by the rippling gold-brown of giant kelp, I’ve been studying what happens on a molecular level when kelp, a seaweed that creates huge underwater forests, ages and decays. Inside kelp cells and tissue, what signals precede the onset of deterioration? How does kelp function change with age? How does older tissue interact with younger tissue? These are all questions I aim to answer as a rising 5th year PhD candidate in USC’s Marine and Environmental Biology program under the tutelage of Dr. Andrew Gracey and Dr. Sergey Nuzhdin.

At face-value, from this line of work, I could theoretically push back kelp death. This could keep kelp’s organic carbon from re-entering the atmosphere in its inorganic, greenhouse gas form, helping counteract climate change. It could also make kelp more cost-efficient as a sustainable source of food, chemicals, bioenergy, etc. or make giant kelp forests more permanent as a habitat. But my research (and this blog post) is about more than preventing death and decay. It’s about life.

Senescence, or the process of aging and biological decline, is intrinsically tied to life. Simplistically, senescence happens when an organism is either overwhelmed by environmental stress and/or prioritizes new life over the maintenance of existing structures. Especially in the case of the latter, new energy and resources will stop being produced in or sent to old tissue and will instead be focused toward new tissue. Oftentimes, the old tissue will even send its broken down resources to areas of new growth for recycling. This requires communication between old tissue and the tissue starting new life, whether that’s the reproductive organs (new organism) or somatic proliferation centers (new growth). In some cases, this signaling is so important that removing senescent cells can lead to delayed or abnormal growth and repair.

Thus, beyond extending kelp life, I am hoping my research into kelp senescence will help us support new kelp growth.

Let’s forget about kelp and all its usefulness as a basis for ecosystems and sustainable economies. Just for a second.

This summer – my third summer at the Wrigley Marine Science Center – and with my research subject of aging, I’ve encountered an inevitable, obvious, but easy-to-forget reality: I’m getting older. And something that’s really dawned on me as I’ve aged is this: what you give and communicate can be just as important as what you build for yourself. Especially when it comes to whoever comes next.

This summer I’ve made more of an effort to interact with younger students and scientists. I’ve been mentoring two wonderful undergraduates through their own chosen research projects. One of their projects is on a topic I know little about – we’re literally learning the subject matter together, and the most valuable things I can give him are the skills to find the resources he needs and support through research’s challenges and disappointments. In return, he’s given me the humility to remember there’s always so much more to learn and the confidence to go out and learn it. My other undergraduate is coming into research from a completely different background – he is literally stepping out of his comfort zone to build interdisciplinary skills and knowledge. And while I help him through the molecular biology of his project, he’s reminding me the importance of communication and considering things from more than your own perspective.

In addition to undergraduate mentorship, I’ve been helping with outreach groups visiting the Wrigley Marine Science Center. USC Sea Grant and Wrigley are great about providing young students access to an amazing slice of nature and science, and I’ve been honored to be with students when they go on their first snorkel in the ocean. I was able to see kids go from being hesitant to jump into the sea to trying their hardest (and failing) to dive under the surface of the water in their extremely floaty wetsuits. I saw them go from desperately grabbing for me in 1 foot of water to excitedly watching bat rays in 15 feet of water. One was all smiles and bright eyes as they told me that now they wanted to become a marine biologist. All of this has been as valuable a part of my summer as my research. Because what would be the point of all my research if it didn’t somehow eventually all lead to the unbridled happiness of children absorbing the beauty of nature?

By no means is my scientific work close to being done- for all my talk of aging, I’m still an early career researcher. Don’t reroute your resources from me yet. You will hopefully see me gearing up in my scuba equipment and swimming through kelp forests for many years to come. But I hope you’re just as likely to see me chatting with an undergraduate about developing their research or leading a group of first-time snorkelers. Because for me, aging is an increasing realization that I have so much more to learn, share, and give.

Inessa Chandra is supported by the Victoria J. Bertics Graduate Fellowship Fund.