Escaping Extreme Heat in Los Angeles: What makes one park cooler than another?

The first two weeks of July of 2023 have seen a constant stream of anxiety-provoking news headlines pointing to record-breaking heat in metropolitan areas around the United States. Unfortunately, these headlines leave little work for me to do in justifying the importance and urgency of studying measures to protect the public from extreme heat.

My name is Aviva Wolf-Jacobs, and broadly speaking, I am interested in how urban green space can be used as a tool to promote public health and environmental justice in cities. For the purposes of my work, the term urban green space refers to trees, parks, grass, and other types of vegetation or natural greenery lining streets or inhabiting open spaces in metropolitan regions.

As a PhD student in the Population, Health and Place program at USC, I work with Dr. John Wilson from the Spatial Sciences Institute in the Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and Dr. Rima Habre from the Population and Public Health Sciences department at the Keck School of Medicine. My dissertation research looks to zoom in on the urban green space happenings around Los Angeles as they relate to health, wellness, and social equity in the context of climate change.

It is unlikely that anyone reading this blog post is a climate change denier, but I’d imagine that any disbelief would be extinguished by the following information:

- Over 2300 heat records from Florida to California have been broken since June 10th, 2023.

- Some recent extreme heat events have been particularly horrifying, including hiking trail closures in Phoenix, AZ due to unshaded trail areas reaching up to 140° Fahrenheit. At the time this blog post was written, Phoenix was in the midst of a 19-day streak of temperatures over 110° Fahrenheit.

- Cities in California, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, Minnesota, and Louisiana, just to name a few, have all seen record daily high temperatures this summer.

- The 4th of July this year is said to be the hottest day on Earth in over 100,000 years.

These high temperatures are projected to hold steady and potentially get worse in many parts of the U.S. for the remainder of this summer and in summers to come. Extreme heat is becoming hotter, more frequent, and more prolonged with anthropogenic global warming.

Extreme heat is the “single largest cause of weather-related fatalities” according to the United States Weather Service. Exposure to extreme heat can cause dehydration, physical and mental stress, heat stroke, fainting, cramping, and heat rash. Heat exposure can also exacerbate existing respiratory, cardiovascular, genitourinary, and diabetes-related medical challenges.

Older adults, young children, people with underlying health issues, and individuals without access to housing or air conditioning are especially vulnerable. Communities of color and other historically marginalized groups also tend to be more vulnerable to extreme heat due to environmental disparities stemming from discriminatory historic zoning and banking practices. Individuals living in highly developed, densely populated regions also face the urban heat island (UHI) effect. The UHI effect describes how areas predominantly covered by buildings and impermeable materials such as cement and metal trap and re-emit thermal energy, causing higher temperatures for longer time periods as compared to rural surrounding areas. Effective relief from extreme heat should be available and easily accessible for everyone, especially in urban settings.

Most people can attest to the value of public parks for cooling off on days of extreme heat. City planners, community members, and other individuals influencing the future of urban sustainability should have as much information as possible to maximize the community benefits of changes they make to parks in the urban environment. That is where research can play a critical role.

Thanks to the Wrigley Institute’s generous support, I have been able to spend this summer as a Wrigley Graduate Fellow trying to understand how the characteristics of public parks either promote or hinder their heat mitigation, or cooling potential. This study aims to identify the specific role, or weight, that various park characteristics, such as tree canopy cover and water features, have in promoting the cooling benefits of public parks. My hope is that the findings from this study will be an asset for understanding which specific park features should be prioritized in future urban greening endeavors.

My research uses geographic information systems (GIS) technology, a set of tools and software that allow for the visualization and analysis of 2D and 3D satellite imagery to understand what level of heat mitigation is taking place within parks, and what types of land surface cover and other cooling-related features can be found in specific public parks.

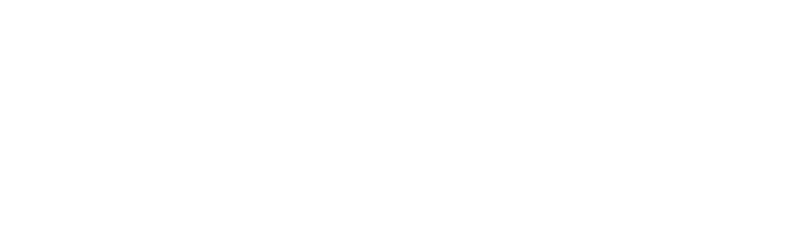

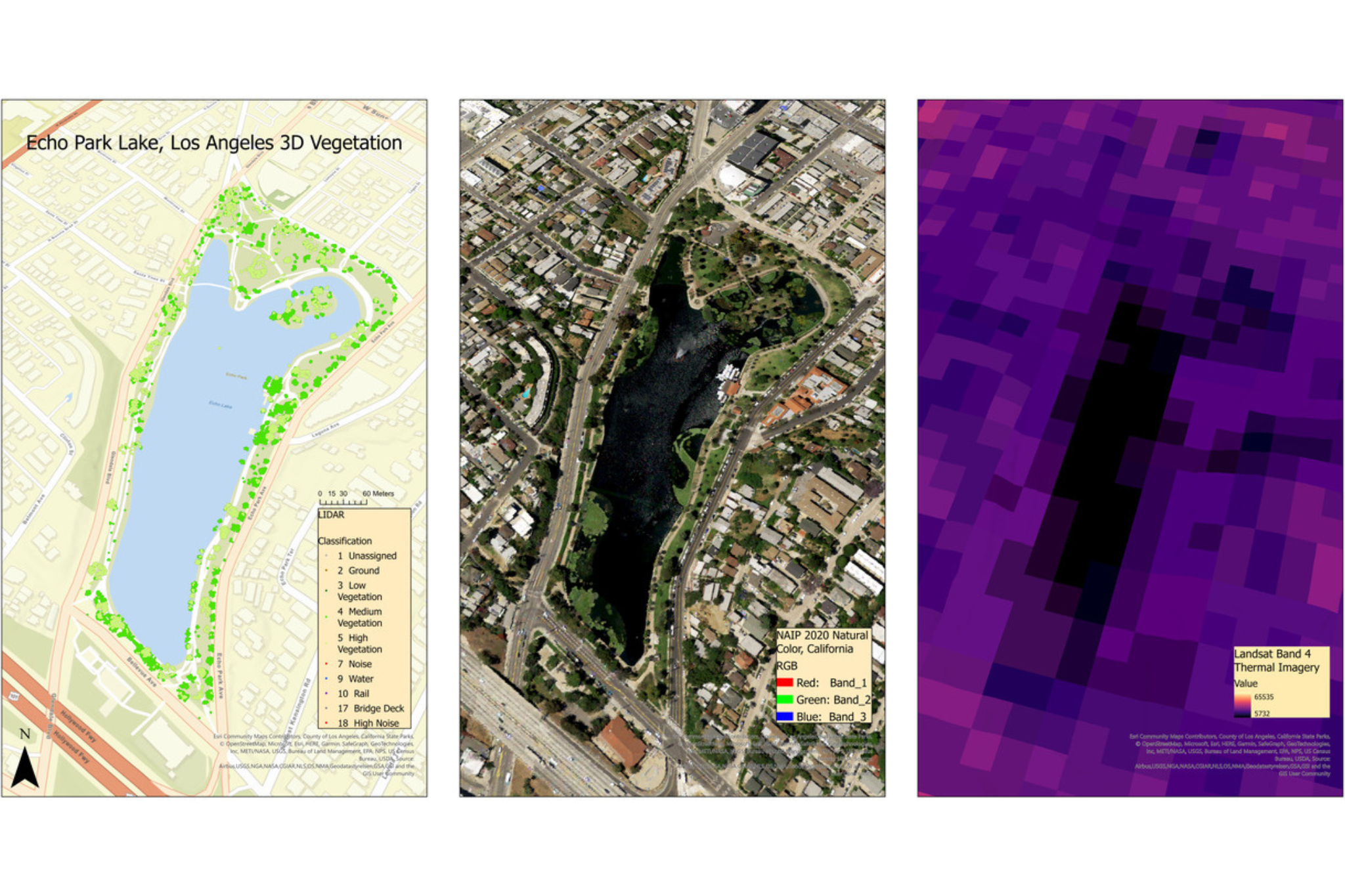

Using ArcGIS Pro GIS software, I have been able to select a subset of public parks in the city of Los Angeles that are ideal for this study due to a variety of geographic factors and conditions that help control for cooling factors that do not relate to my study questions. Figure 1 above shows Los Angeles City public parks fitting park area and ocean proximity criteria. For each of the selected parks, I’m using thermal imagery from hot summer days and GIS tools to calculate the temperature difference between the park and its surrounding area, which is also known as the park cooling island (PCI) effect. Below, Figure 2 illustrates various types of satellite imagery I am using to analyze vegetation composition and temperature characteristics for Echo Lake Park.

I’m using publicly available 2D and 3D satellite imagery including the imagery shown in Figure 2, along with GIS vegetation classification analysis tools, to determine values for different park characteristics, including the percentage of surface area covered by grass, tree canopy cover, vegetation of different heights and volumes, impervious surface cover, etc. for each park of interest. I will then analyze these values in relation to PCI effect values to try to better understand which park characteristics are most strongly associated with park cooling potential.

Simply put, I seek to use GIS technology to better understand current relationships between parks’ environmental and vegetative characteristics and their cooling potential in Los Angeles. Hopefully, these findings can help to inform how public parks in similar climates might be altered, expanded, or created to best help the public keep cool on hot days and nights.

Aviva Wolf-Jacobs is supported by the USC Dornsife Wrigley Institute Graduate Fellowship.