In the Eye of the Storm: Centering cities in the climate crisis

I landed at Ninoy Aquino International Airport on a rare sunny day. It was June, after all, and the balmy weather would soon give way to typhoon season. In the Philippines, within and beyond Metro Manila, torrential rains through September constitute an inescapable reality of life on the archipelago. While severe flooding on SLEX (South Luzon Expressway) may seem like a ‘great equalizer’ as it slows every tricycle and SUV to a halt, it also sheds light on the inequalities etched deeply into the cities by way of the built environment, from chronically underperforming wastewater management systems to the gradual disappearance of green spaces to make way for high-rise condominiums and shopping malls.

To a balikbayan like me, these large infrastructural changes can be disorienting. At the same time, as a scholar of global governance and environmental politics, I see these evolutions with a deeper appreciation–and perhaps, apprehension. As the country and its people experience the ramifications of unfettered local and global industrialization and consumption, we must look critically at the gaps between what national government leaders declare vis à vis the international community, and what changes do or do not occur at the most local level.

Internationally, the proliferation of natural disasters in conjunction with environmental mismanagement and destruction have been central themes in climate and sustainable development negotiations among global leaders, as countries across both the Global South and Global North suffer extreme weather events. Scientists, policy practitioners, and activists alike have called out national governments for their failures to consistently meet standards established in prior agreements, and to sign and commit to more aggressive measures to mitigate one of the defining crises of our time.

* a Filipino visiting or returning to the Philippines after a period of living in another country

Some of these critiques originate from actors within the governments of those same countries that have reneged, or are falling behind on commitments. In the years following the signing of the Paris Climate Accords, city leaders have grown increasingly vocal about how local governments are the on the frontlines of climate change, as those directly responsible for the provision of public services and resources especially during emergencies. In the same vein, local governments are advocating to have international agreements and national-level policies integrate local government expertise in decision-making, allocate more resources for cities to better prevent and respond to environmental challenges, and to take seriously the growing practice of subnational diplomacy. With a crisis that defies the territorial boundaries of nation-states, there is growing acceptance of the need for localization: both integrating local expertise into the achievement of the global frameworks, and supporting bottom-up approaches to advancing global goals, from the Paris Agreement to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

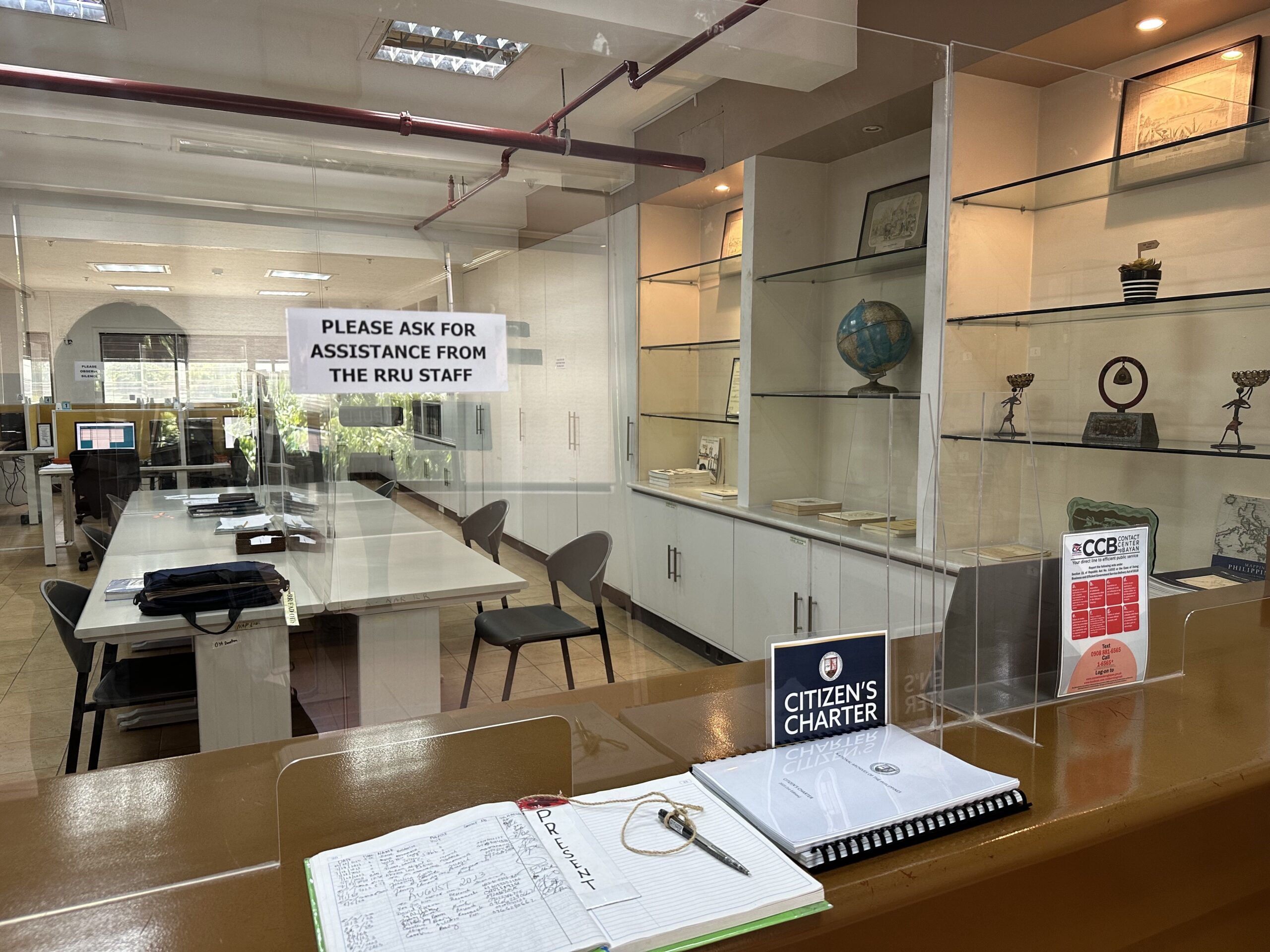

With the support of the Wrigley Institute for Environment and Sustainability, I return to the Philippines and Southeast Asia to study this particular phenomenon from the local perspective: whether and how city governments are innovating–beyond national governments–to translate international agreements and their embedded standards in ways that serve (or do not) the needs of cities. I am currently conducting archival research and identifying key local stakeholders as potential interviewees for outreach to develop case studies that provide deeper insight on the linkages between global and local governance. I will also be traveling to other cities in Southeast Asia to generate cross-comparative studies of intra- and inter-city efforts in localization.

There has been a tremendous amount of research on how cities in Europe, North America, and Latin America are localizing climate initiatives. I focus on Southeast Asia to recenter the narrative on a region that has historically borne the brunt of the world’s most catastrophic natural disasters, and yet continues to receive limited attention in terms of how cities in the region are pioneering mitigation and adaptation strategies that are locally-driven. In the Philippines, while executive powers oversee key national policy institutions such as the Climate Change Commission or the National Economic and Development Authority, several written codes and circulated memoranda since 1991 have institutionalized climate change adaptation as a regular function of local governments. As of November 2022, 80% of local government units (LGUs) in the Philippines have formulated Local Climate Change Action Plans (LCCAPs) in efforts to mainstream policy mandates on climate change and disaster risk reduction. The Department of Interior and Local Government published process guides for the creation of these LCCAPs, which were directly informed by the work of United Nations Habitat, greenhouse gas inventory development in accordance with the Paris Agreement, and by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). These are only some examples of how international norms on climate and the environment can shape decision-making at the most local level.

Whether these plans translate into observable outcomes for the community, and whether such localization efforts exceed national goals and measures, are two central pieces of the research puzzle and remain to be seen. These questions are particularly important in this year of transition with concurrent general and local elections held in 2022. The physical changes in the country’s capital are reflections of deeper, gradual socioeconomic and political transformation, and the coming years will reveal the implications for environmental and social welfare.

The 2022 World Risk Index has ranked the Philippines with the highest disaster risk values out of 193 countries, based on combined metrics of exposure, vulnerability, susceptibility, and capacity. Research to date on localization signals the importance of assessing subnational level variation in both the experience of climate outcomes, and the capacity to address them. It also reminds us of the need to consider who implements these global policies, and what internationally negotiated goals mean for local communities. As I continue to conduct fieldwork for the remainder of the year, I hope to not only address the central question of my dissertation, but also shed light on the complex interactions of global and local governance and move beyond national government-centric views on how to advance more just and sustainable institutions and policies.

Gaea Morales is a fifth-year PhD candidate in Political Science and International Relations and a 2023 Wrigley Institute Graduate Fellow at USC. Her dissertation focuses on the role of cities as actors in global governance in the realm of sustainable development and climate policy and politics, and more broadly the question of how global governance ideas translate into local action. Gaea Morales is supported by the Diane Sonosky Montgomery and Jerol Sonosky Graduate Fellowship for Environmental Sustainability Research.