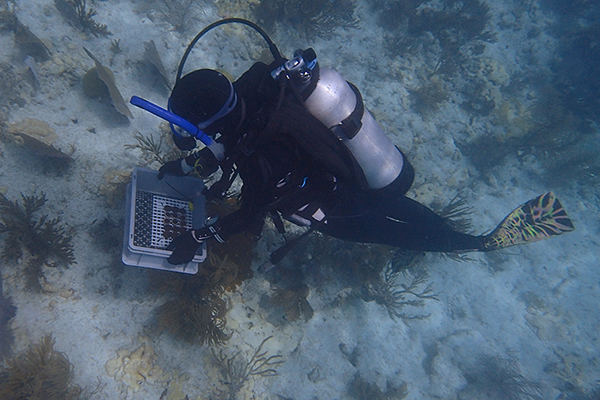

Biological Sciences professor works with Wrigley Institute to protect fragile reef ecosystem

As a marine biology major in New York state, Carly Kenkel wasn’t quite sure how she wanted to use her degree. Then she participated in a National Science Foundation-funded Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) at Florida’s Mote Marine Laboratory. There, she studied coral microbiomes—and she was hooked.

Kenkel went on to earn her Ph.D. in evolutionary ecology at the University of Texas at Austin. Now the Gabilan Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences in USC Dornsife, she is a faculty affiliate with the Wrigley Institute and works to protect vulnerable coral reefs around the world.

“I had always been fascinated by variation. I saw that some coral were bleached while neighboring colonies were unaffected, and I wanted to know why. I learned the background and skills in grad school to finally start answering that question,” she says.

Although many people think of corals as plants, they’re actually animals that are related to anemones and jellyfish. They shield their soft bodies in a calcium-rich shell—the hard material most people think of when the word coral comes to mind. When corals gather in large colonies, they form reefs. Aside from being stunningly beautiful, reefs are crucial to ocean ecosystems. They house countless forms of sea plants and wildlife and provide nurseries for many species, including those that serve as food for humans.

According to Kenkel, these reefs already experience significant stressors, even in what we might think of as friendly environments. They deal with storms, predation, disease events, and seasonal warming. “But now they have to handle all this under the increasing chronic pressures of ocean warming and acidification—not to mention that these processes also intensify storms and other stressors,” Kenkel says.

The result has been a drastic and potentially catastrophic decrease in reef size worldwide. In the Caribbean alone, coral cover (as a percentage of ocean-floor surface area) has declined into the single digits. On the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, scientists are seeing an especially disturbing trend: what Kenkel calls “recruitment failure,” or a marked decrease in new baby coral.

The most visible manifestation of reef damage is “bleaching,” a phenomenon named for the way it causes corals to lose their famously vivid colors. Corals are symbiotic organisms: colorful algae live in their tissues and, through photosynthesis, produce sugar and other products that form the bulk of corals’ food supplies. The algae are also what give corals their colors. Acidification and ocean warming are killing off the algae, turning the coral white. While temporary bleaching is survivable, the extended absence of algae will eventually starve and kill a coral. And this is precisely what is happening in our climate-changed seas.

Much of Kenkel’s research involves investigating biomarkers and determining how they affect corals’ response to today’s extreme stressors. She joined USC Dornsife and the Wrigley Institute for several reasons, including because the location places her midway between Caribbean and Pacific Reefs. She also loves the cultural diversity of Los Angeles and USC itself.

In addition, her post with the Wrigley Institute has helped her expand her work, thanks to the unique features of local ecosystems. An anemone called Anthopleura, which lives in Southern California’s intertidal zones, is a thermally tolerant coral cousin. Kenkel hopes that she and her graduate students can use Anthopleura to glean insights for coral preservation and restoration. She has already developed simple tools that researchers can use to detect heat stress in corals. These could serve as an early-warning system to help marine biologists identify which reefs need the most attention, before they reach the point of bleaching or other significant damage.

But you don’t have to be a scientist to help save coral reefs, Kenkel points out.

“Greenhouse gas emissions are the single greatest threat to reefs,” she says. “Individual action to reduce your own carbon footprint is good, as is promoting education and awareness, but supporting policy that supports reefs is the most critical. And those are all things that anyone can do.”